Regional Folk Pysanky

Article

Regional Folk Pysanky

Article

In 2017 I wrote an article about the characteristics of folk pysanky in various regions of Ukraine; this was printed in the newsletter of the Ukrainian Museum and Archives of Detroit. It is a brief survey of some parts of Ukraine; you can download it here. I have incorporated parts of this article into the various sections of my web site. The text is below.

Traditional Ukrainian Folk Pysanky

Every Ukrainian knows at least a little something about pysanky–perhaps a legend about their origins, perhaps the etymology of their name (pysanka comes from the verb “pysaty,” to write, because, like icons, they are written and not painted). What many are not aware of is that pysanky are of two types: traditional folk pysanky, and what the Ukrainians call “avtorsky” pysanky. The former are traditional designs handed down over many generations; the latter are original designs created by an artist, often incorporating traditional motifs.

Avtorsky pysanky are the type most often seen in the Diaspora: intricate, colorful designs created by the individual pysankar or pysankarka. Although most Ukrainians have tried their hand at writing pysanky at least once, most of the pysanky you see–in shops, catalogs or china cabinets–were created by professional pysanka artists.

Traditional Ukrainian folk pysanky are another matter altogether. The designs are often simple, and color palette limited--these pysanky were created not primarily to please the eye, but to communicate with the gods. They were talismanic objects, whose designs and symbols stretch back into Ukrainian prehistory, into

pre-christian times. They were written by the women of each household to protect their families, to chase away evil spirits, to ensure the fertility of their fields and animals, and to ensure the return of the warming sun each and every spring.

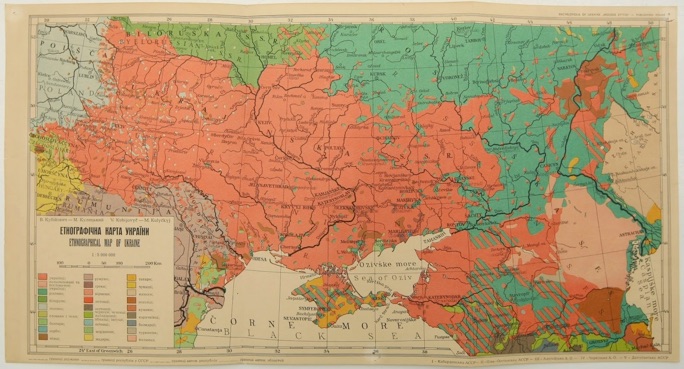

While the basic motifs found on pysanky are fairly similar from one region of Ukraine to the other (and were discussed at length in the Spring 2013 newsletter), there are definite regional differences in pysanka design.

Hutsulshchyna

The Hutsul people can be found in the high Carpathian mountains, in three oblasts of Ukraine–Ivano Frankivsk, Zakarpattia and Chernivtsi. They are know for being master craftsmen, and create beautiful embroideries, metalwork, woodwork and pottery. Their pysanky are distinct for the intricacy of their designs, which is actually a fairly recent development. Hutsul pysankarky began selling their pysanky in the 1800s, first locally, and then eventually in many cities in the Austro-Hungarian empire. The more intricate pysanky sold better, so they began to create more and more of them, and now those designs predominate.

Hutsul pysanky exhibit several other characteristics. The use of animal motifs is more common than in other regions. You will often see birds, fish, deer and horses on Hutsul pysanky; the latter two are sun symbols–our ancestors believed that either a stag or a horse carried the sun across the sky–and are seen only on Hutsul pysanky.

Hutsul pysanky are also known for their use of resheto (cross-hatching); in most other regions, solid colors or stripes are more commonly used as “fill.” This example from the village of Stari Kuty, illustrates the Hutsul use of resheto.

In several areas of Hutsulshchyna, village scenes can be found on pysanky, including those showing ordinary human figures (rather than supernatural beings).

The Hutsuls share with the Bukovynians a love of churches and chapels. Not only do they build lots of them–many Hutsul families have a small “kaplytsia” near their house–but they often portray them on pysanky.

The late Eudokia Kushnierchuk, a noted Detroit area pysankarka, was born in Kosmach and learned to write pysanky there. Her pysanky, written in Kosmach style, used the traditional Hutsul colors of yellow, orange, and dark brown, with occasional green highlights.

In recent times Hutsul pysankary have switched to a brighter color palate, that of yellow, red, green and black.

These modern “Kosmach” pysanky now flood the market, and are squeezing out the older forms.

Lemkivshchyna

The Lemko people are also mountain people, but most of their ancestral lands now lie outside of the modern borders of Ukraine. There are some in Zakarpattia oblast, and many reside in their old villages in the Priashiv region of Slovakia. Those who once lived in Poland were “resettled” after WWII–some repatriated to Ukraine and scattered throughout that nation, others sent to western areas of Poland.

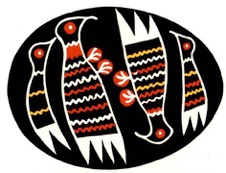

While Lemky do write pysanky using an ordinary pysachok, they are renowned for their “drop-pull” pysanky. These are created using a different tool–a straight pin or nail in a wooden handle. The tool is used to apply molten wax to the egg. Dots, teardrops and commas can be created, depending upon whether the wax is “pulled,”and how it is pulled. All the shapes on the pysanka below were created with this technique.

Lemky favor bright colors, and their pysanky are rarely multicolored, unlike the one above. They create not only stars, suns and flowers, but human figures, waves, intricate borders and birds (like the storks below).

Boikivshchyna

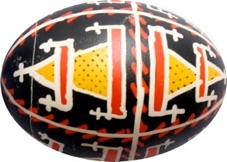

The Boiky are the third group of Ukrainian mountain dwellers; their lands are divided between Lviv, Ivano Frankivsk and Zakarpattia oblasts. While they sometimes use the drop-pull technique, most of their pysanky are written with in the usual fashion (linear batik).

Boiko pysanky are geometric, with simple motifs: S shapes, curls, stars. There is little coloring in--space is filled with dots, dashes, small circles, squiggles and lines. The lines are usually white on a colored background; occasionally a second color might be used, as in this “Windmill” pysanka:

Or in this starry pysanka:

Bukovyna

Most of Bukovyna lies in the modern Chernivtsi oblast; the rest is in Romania and Moldova. Bukovynian pysanky are beautiful and colorful, and share with the Hutsuls a love of resheto and church motifs.

One common characteristic of Bukovynian pysanky is use of the diagonal division and diagonal bands. Sometimes the bands wrap around the entire egg; other times they are just on one face. There might be a single diagonal band encircling the pysanka:

There might be two intersecting diagonal bands:

Another popular type of Bukovynian pysanka is the “rooster” type. That is the name given to those pysanky with certain goddess motifs: sigmas (S) with wings. These “kucheri” usually have a crown, which apparently looks like a rooster's comb.

A common and characteristic motif found on Bukovynian pysanky is the compound, or complex, cross. This is an equilateral cross which has further crossing at the end of each crosspiece. It is an ancient, pre-christian sun symbol.

While the simple variant of this cross (above) can be found in other regions (e.g. Hutsulshchyna), the more complex variant below is rarely seen outside of Bukovynian pysanky.

A note should be made about the colors found on Bukovynian pysanky. Dark red/mahogany backgrounds are popular, as opposed to the black and dark brown preferred by the Hutsuls. The pysanky also appear bright because of the frequent use of pinks, blues and greens in fairly large amounts.

Pokuttia

The pysanky of Pokuttia, the lowland region between the Carpathian Mountains and the Dnister river, are similar to those of the Hutsuls, but generally less intricate. There is huge variety in Pokuttia–each village has its own style, color schemes, and favorite motifs. In some areas simple one-color pysanky with ancient motifs are the preferred type.

In others, multiple colors and more complex designs predominate. Resheto is frequently used in Pokuttia:

Pokuttian pysanky are often made more colorful by the use of “slezy” (tears):

Slezy are irregular splotches of color added by dripping wax onto the pysanka. In other regions the slezy are large and red; in Pokuttia they are multicolored and a bit smaller.

Volyn

Located in the northwest corner of Ukraine is Volyn. The earliest published pysanky were those collected by Olena Pchilka (Olha Kosach, the mother of Lesia Ukrainka), and included in her folio of Ukrainian embroidery in 1876.

The Volynians favor a red, yellow and green colors. The motifs are ancient, and include ruzhi (stars) and plants.

Volynian pysanky often use the “sakvy” or saddlebag division.

Sokal

The Sokal region is a small area just south of Volyn; Korduba called it “Halytska Volyn” in his ethnographic work. It is renowned for its black embroidery and its unique pysanky. Prior to the 20th century the pysanky from this region were similar to those of Volyn and Halychyna. In the early 1900s, china painting became popular among the young women of the area, who adapted these floral designs to pysanky, sometimes in a traditional manner (e.g. the vazon/flowerpot):

Other times the designs became completely free form:

This naturalism was applied to other subjects, too, like this “rak” (crayfish) found by Korduba:

Podillia

Western Podillia (Ternopil oblast) has preserved some truly ancient pysanka motifs; on their black pysanky you will find representations of the Berehynia

and of the Zmiya (Serpent god).

In eastern Podillia (Khmelnytskyi and Vinnytsia oblasts) the pysanky are more colorful; plant and archaic (hand of god, pavuky, tortoise) motifs are quite common. The sakvy division is popular here, and stripes are often used as color fill, as in this “Hand of God” pysanka:

Many hundreds of these pysanky and their designs have been preserved in manuscripts and museum collections, both in Ukraine and in Europe.

Podniprovia

This is the heart of Ukraine, the lands which lie along the Dnipro river. Floral motifs and the eight pointed ruzha predominate here. The pysanky are quite colorful; backgrounds tend to be dark, except in the Poltava region where reds and green predominate. One of the best known pysanky from this area is called “Magpies.”

An example of the brightly colored pysanky from Poltavshchyna is this “bezkonechnyk” (never ending line).

Kulzhynsky, in 1899, published illustrations of several pysanky from Shuliavka, then a village near Kyiv with its unique pysanka style. This is one of them:

Sumy

The pysanky of the Sumy region in northeast Ukraine, like those of nearby Poltava, are brightly colored, and plant (particularly floral) motifs predominate. Among these, though, are found a lot of “white” pysanky (borshchivky).

These are pysanky which have been written in the usual manner, and then lightly etched (using sauerkraut juice) to remove the dyed shell and make the background white. This pysanka is an example of a white vazon (berehynia motif):

The pysanka below has an “ox eye” motif.

This motif is found throughout Ukraine, and is thought to represent the eye of the god Veles, who was the protector of farm animals.

Sloboda

This region in in eastern Ukraine which straddles the border with Russia, and includes parts of Kharkiv, Sumy and Luhansk oblasts. Pysanky from the Kharkiv area tend towards plant motifs, as in neighboring Podniprovia:

The Kursk area in the east is now a part of Russia. The pysanky from this region are quite interesting and intricate. This is an example of a sorokoklyn (40 triangles) design:

Kulzhynsky recorded a number of pysanky from the village of Kozatska Sloboda in this region; they have designs in red and yellow, with lots of sosonka/pine branches, stripes and fringe, as in this example.

Kuban

Kuban is now a part of Russia, and is to the south and east of present day Ukraine, bordering the Black and Azov Seas. The pysanky from this region favor black and red colors and ancient motifs. An example is this berehynia:

This pysanka is covered with ruzhi, eight pointed stars that are ancient symbols of the sun god, Dazhboh.

Author’s note: this is a fairly superficial survey of pysanka styles. Volumes could be written on Hutsulshchyna or Pokuttia alone, and I’ve had to leave out many regions for lack of space.

The illustrations in this article are taken from numerous sources: Binyashevsky’s published and unpublished works, Kosach’s folio page, Korduba’s essay, Oleh Kirashchuk’s illustrations of Pokuttian pysanky and Yevhenia Hayova’s photos of pysanky from the Sniatyn region. I’ve also included many of my own photos, both of pysanky I’ve written, and those I’ve photographed in the collections of others.

––Luba Petrusha

Regional Characteristics of Ukrainian Folk Pysanky