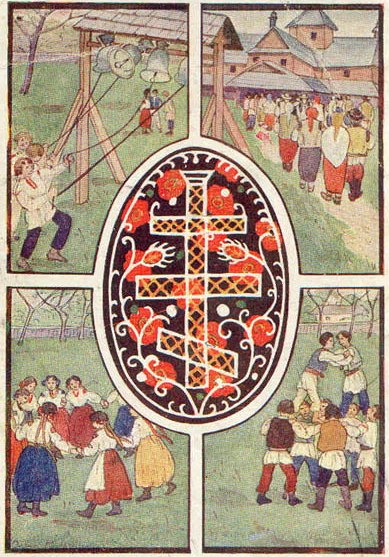

Pysanka Traditions

In the countless centuries that Ukrainians have been creating pysanky, many traditions have grown up around their creation, sharing, and talismanic uses. I have tried to cover these on the following pages, and have included on this site my translations of the relevant pages from Oleksa Voropay’s “Folk Customs of Our People.”

The customs described here were followed closely throughout Ukraine in the pre-Modern era, i.e. up until perhaps the mid-19th century, and continued to be practiced in some regions until after WWII. They are rarely practiced today in their original forms, although some continue to be honored in Ukrainian villages.

Why did these traditions change?

With the coming of science and technology and a more modern world, folk life began to change, as beliefs in magic and the supernatural diminished. The old ways were viewed as mere superstition, and were either forgotten, or followed in part, even as their talismanic and supernatural underpinnings were forgotten. Most people simply no longer believed in demons and evil spirits, nor in the magical properties of eggs.

Another factor pushing change was the commercialization in the 1800s of pysankarstvo in some regions of Ukraine. While most people continued to create pysanky for their own use, others began creating them for sale, not just to neighbors, but also for markets in neighboring cities and countries. Foremost among the commercial pysankary were the Hutsuls, who sold their wares in Ukraine and in nearby areas of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

In the twentieth century, in eastern and southern Ukraine, religion and national identity were suppressed as formal policy by the USSR. Pysankarstvo died out in many regions altogether, as it was viewed as a religious practice, unlike folk painting, embroidery and woodworking, which were not only allowed to continue to be practiced, but were actively commercialized and mechanized. (After WWII, when the USSR annexed western Ukraine as well, similar suppression of pysankarstvo and Ukrainian identity occurred there as well.)

And, most recently, pysankarstvo has been fully transformed into both a folk and fine art. Modern tools and dyes have taken over, and few people remember how to create traditional pysanky, much less the rituals involved with their creation. While a revival of the folk pysanka is occurring in Ukraine, many artists have taken up pysankarstvo and are creating beautiful, albeit miniature, works of pysanka art.

This section is still a work in progress, but the following is an outline of what I have so far:

Oleksa Voropay (Олекса Воропай) was a Ukrainian ethnographer who included much ethnographic information about pysanky, pysankarstvo, and krashanky in his book «Звичаї Наших Предків» (“The Folk Customs of Our People”). I have translated the relevant portions of that book and included them in a separate section here:

Back to History/Traditions/Legends home page

Back to MAIN Pysanka home page.

Back to Pysanka Index.

Search my site with Google