Kyivan Rus’

Київська Русь

Kyivan Rus’

Київська Русь

There are no known examples of any kind of pysanky from the proto-slavic period (prior to the VII century AD). We do know that the early Slavs believed that everything began with the egg. Not only was the egg a symbol of life, but its components symbolized the parts of the universe: the shell symbolized the heavens, the egg white symbolized water, and the yolk represented the earth.

As Manko wrote: “ In ancient beliefs, the cosmic egg, from which everything emerged, was born from and divided by a serpent–god of the earth, of the underworld, and of fire. Thus, an egg, the symbol of the serpent, the male deity of the earth, who was considered, along with the original goddess mother, to be the creator of everything alive on earth–was one of the main elements of a pagan spring holiday dedicated to the spirit of rebirth.”

It is thought that the egg’s status as as a symbol of rebirth was the reason that it was often placed in graves and used in burial rituals, a practiced that has continued into modern times. In early Slavic belief, the egg represented the passage of the deceased into the realms of the serpent.

In the later Slavic period, the sun god (Dazhboh) was among the most important of all the deities; birds were the sun god's chosen creations for they were the only ones who could get near him. Humans could not catch the birds, but they did manage to obtain the eggs the birds laid. Thus, the eggs were magical objects, a source of life. The egg was also honored during the spring festival1, Velykden’––it represented the rebirth of the earth. The long, hard winter was over; the earth burst forth and was reborn just as the egg miraculously burst forth with life. The egg, therefore, was believed to have special powers.

No pysanky have been found in any excavations from the period of Kyivan Rus (9th to 13th centuries)2. Yet decorated eggshells have been found in graves in neighboring Poland, dating to the 10th through 13th centuries, and painted eggs have been found in graves throughout Europe, Africa and Asia.

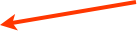

Although we have no actual pysanky remaining from the Kyivan period (the oldest know pysanka only dates back 500 years), we do have ceramic representations of the pysanka (left, from Manko’s “Ukrainian Folk Pysanka”) dating back to the 9th century, and some seventy have now been found throughout the former territories of Kyivan Rus (from Podniprovya to Halych). Many of them were found in the excavated graves of both children and adults.

These ceramic eggs were common in Kyivan Rus, and had a characteristic style. They were slightly smaller than life size (2.5 by 4 cm, or 1 by 1.6 inches), and were created from reddish pink clays by the spiral method. The majolica glazed eggs had a brown, green or yellow background, and showed interwoven yellow and green stripes, thought to represent the sosonka (an evergreen plant which creeps along the ground and symbolizes everlasting life; it is a common motif on pysanky to this day).

Example of Kyivan-Rus era ceramic pysanka from Binyashevsky

The eggs made in large cities like Kyiv and Chernihiv, which had workshops that produced clay tile and bricks; these tiles (and pysanky) were not only used locally, but were exported to Poland, and to several Scandinavian and Baltic countries. (More information here.)

11th-14th c. Clay pysanky (from B.A. Kolchin)

This is an example of a ceramic pysanka of this sort excavated in the village of Pidhirtsi (Підгірці) in the Lviv region; it dates back to the 12th century AD.

It is believed by many3 that pysanky may have been created in Ukraine since pre-Christian times, and perhaps as far back as Trypillian times, although there is no evidence for the latter. Most of the symbolism of the pysanka is pre-Christian in origin, and the huge variety of traditional pysanka designs, the exquisite intricacy of the designs, and the ubiquity of the practice of pysanakarstvo (there is no ethnic region of Ukraine where it is not an old, established tradition) suggest its great antiquity.

With the advent of Christianity in ancient Ukraine, and via a process of religious syncretism, the symbolism of the egg began to change to represent, not nature's rebirth, but the rebirth of man. Christians embraced the egg symbol and likened it to the tomb from which Christ rose. With the official (and state mandated) acceptance of Christianity in 988, the decorated pysanka continued to play an important role in the rituals of the new religion. Many symbols of the old sun worship survived and were adapted to represent Easter and Christ's Resurrection, and the symbols and motifs on the eggs were re-interpreted (and often re-named) to fit with the new dogma.

It should be noted that, although Ukraine officially became a Christian nation in 988, actual acceptance of the new Christian religion was a much longer process. As in many cultures, lip service was paid to the new religion, while the old religion was still practiced in private for some time after the official “baptism” of the country. The symbols on the pysanka thus had a duality of meaning–the official Christian interpretation, and the older, “real,” talismanic pagan meaning.

And, sometimes, the old symbols were hidden among the new, a form of traditional resistance to the new religion. In the Spanish colonies of the New World, sun symbols were incorporated into the decoration of cathedrals, and pagan gods were worshipped as local saints.

The church of La Compañía de Jesús in Quito, Ecuador (Note central sun in dome)

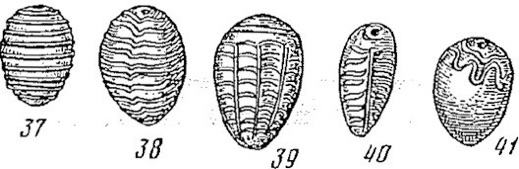

Similarly, in early Christian Ukraine, the old symbols were hidden among the new, and still secretly worshipped. Sun symbols (eight-pointed stars) were often hidden within crosses, as in this pysanka from Kozats’ka Sloboda (Козацька Слобода):

Note the central star within the cross (from Zenon Elijiw)

Old rituals were still practiced, often renamed and then enshrined as “folk traditions” (and sometimes frowned upon by the church). Thus the night of magic and divination in early winter became known as St. Andrew’s Eve, and the midsummer festival (Kupalo) was was called “Ivana Kupalo” (after St. John). Symbols were retained, but given either new meanings or new names. The symbol of the ancient goddess, the Berehynia, continued to be drawn, but was called instead «Kоролева», «Княгиня», or «Панна» (“Queen,” “Princess,” or “Young Lady”).

This representation of the goddess “Berehynia” from Borshchiv, Podillya, is now called “The Queen”

(from Zenon Elijiw)

In time, many of the original meanings of the ancient symbols and rituals were forgotten. They continued to be used and practiced, but with only vague recollections of their former magical talismanic meanings.

__________

1.We should keep in mind that, until recent times, the start of the New Year was generally celebrated in spring, usually on the vernal equinox. The Romans switched it to January 1, while leaving the names of the months the same. (Thus September became the ninth month instead of the seventh, with similar changes for October, November and December.)

This change did not outlast the Roman empire in most of Europe, and most people continued to celebrate a spring new year until the 16th century, when a gradual change occurred. Russia switched over in 1700 by order of Tsar Peter I. Much of Ukraine was under Russian rule at the time, so the practice changed there, too. Those parts of Ukraine under Polish-Lithuanian rule changed over sooner.

A March/April new year is still celebrated in much of Asia.

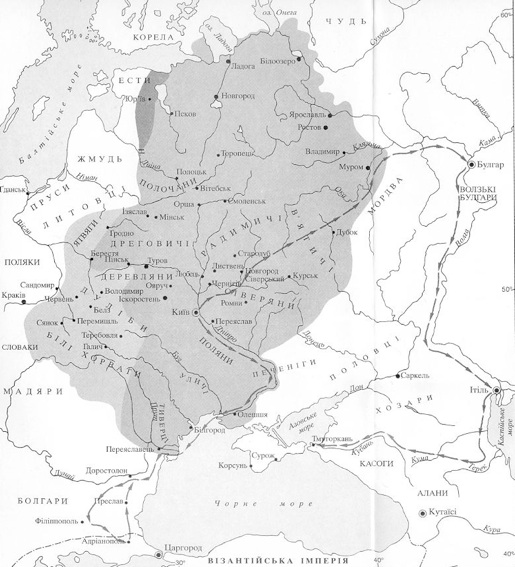

2.Kyivan Rus’ (880 though mid-12th century), at the height of its power, incorporated much of of modern day Ukraine, as well as parts of Belarus and Russia (see map below). Russia was known as “Muscovy” through much of its history, taking the name “Rossiya” (from “Rus”) only in the 16th century, in an attempt to aggrandize its image and early history.

3.There was a school of thought that believed that pysankarstvo, a form of batik, had been brought to Ukraine (and Slavic Europe) from the East, and only took root quite recently, in the 18th century. The discovery of the Baturyn pysanka put lie to this, and the more recent discovery of a 500 year of pysanka in Lviv has demolished it completely. Pysankarstvo appears to be an indigenous folk art.

Kyivan Rus’ in 1054

Back to History home page

Back to MAIN Pysanka home page.

Back to Pysanka Index.

Search my site with Google

St. Volodymyr, the grand prince of Kyiv who forcibly converted Ukraine to Christianity,

flanked by the martyrs Sts. Borys and Hlib (a mural in St. Michael’s cathedral, Kyiv)

Kyivan Rus’ (and early Slavic)

Cross

Star