Osadca

Atanasia “Tanya” Osadca (nee Klym) was not a trained ethnographer; rather, she became fascinated by folk pysanky in the 1960s, and worked hard to track down traditional designs in the ethnographic literature and in Ukraine. She spent her life recreating designs and sharing them through museum exhibitions, books, articles and classes.

Osadca spent much of her childhood in Poland, where she was born. Her parents were both teachers during a time of Polish rule in Halychyna. It was a period of fierce Polonization, and they were not allowed to teach in Ukrainian, and not allowed to teach in Ukraine. Tanya and her sister would spend their summers with their grandparents in the selo.

They became DPs (displaced persons) after the war, and Tanya met the love of her life in Germany. They emigrated to America in 1950, where Bohdan trained as a psychiatrist. He became a military doctor, and she lived in the many places he was stationed.

Tanya's pysankarstvo began as a way to make a few dollars to help support the family while her husband was in training, but she became utterly fascinated by pysanky and they became her passion. She searched out any materials she could find on the subject, even finding a copy of Kulzhynsky's book in a library and carefully photographing all the pages and having them printed. She competed and collaborated with her uncle, Zenon Elyjiw, in finding new sources of traditional designs and in reproducing them.

Her best friend was her sister, Aka, a painter and sculptor. When her husband retired, they moved to Troy, Ohio, so Tanya could be near her. They collaborated on projects, putting together exhibits of Aka's art and Tanya's pysanky. They even took their show on the road to a newly independent Ukraine, where Tanya got to meet ethnographers and pysankarky from all over the country. The demand for their show was great, and it moved from city to city; her pysanky ended up on permanent display in Poltava.

Tanya passed away in 2019. Her pysanky are on display at he Ukrainian Museum in Cleveland, in the display cases her husband, Bohdan, made for her. She left the bulk of her pysanky and ethnographic materials (books, articles, and her own research) to the Ukrainian Museum in Stamford.

Below is an article she wrote (and which I have translated) for UNWLA’s “Our Life” magazine, and which was published in April 1999.

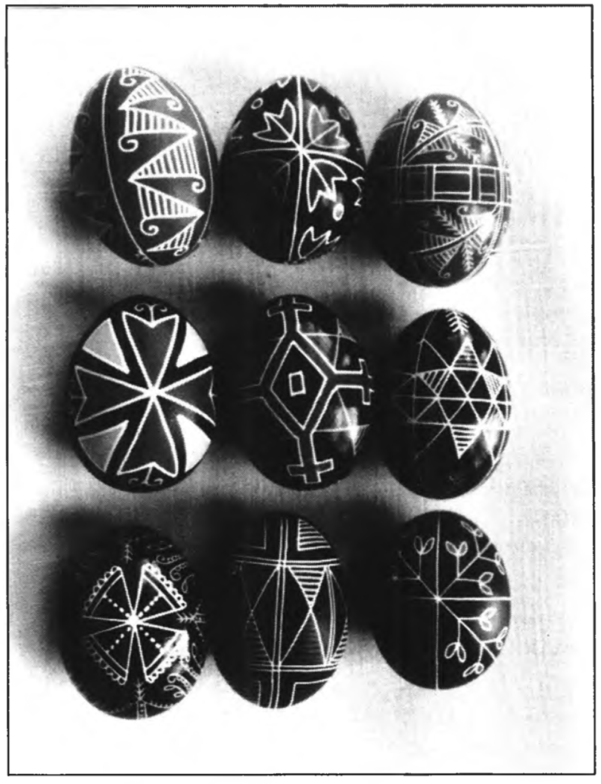

Sokal pysanky of the late 19th century

Sokal Pysanky

by Tanya Osadca

Interest in pysanky began at the end of the 19th century. At that time, the first private and museum collections of folk art arose, including pysanky. By then pysanky from the Sokal region were in the museums of the "Prosvita" Society and Count Dzieduszycki in Lviv. Myron Korduba and Bronislav Sokalskyi, the first researchers of Sokal pysanky, uztilized these collections. Later, the museum collection of "Prosvita" was transferred to the museum of the National Academy of Sciences, and in the 1940s, together with the museum collection of Count Dzieduszycki, it enriched the large collection of pysanky, which today is in the Lviv Ethnographic Museum.

In his work "Pysanky in Galician Volhynia", Myron Korduba described the pysanky of the area "with which he was best acquainted,” that is, the povits in the northern part of the present Lviv oblast, including Sokal povit. Even then, in 1896, Korduba wrote that the custom of pysankarstvo was declining and the result of such decline was an ever-increasing number of krashanky... "the less particular are satisfied with them." Eventually, only a few women were engaged in writing pysanky, and there were villages "where only one old grandmother knows how to write pysanky and she says she gets paid a lot of money for them." The costs of the pysanky varied, depending on the experience of the craftswoman and the desired design. Of course, for writing one pysanka at that time, 2-3 eggs or 3-10 kreutzers were demanded.

Pysanky with a red background were considered by Korduba to be another proof of the decline of custom because... “they require less work.” On those pysanky, we see only two or three colors. Those pysanky were called "written in one wax" or "written in two waxes" in the Sokal region; the pattern was written on them with white and yellow dye on a red background. These pysanky should also include patterns written in white and yellow dye on a black background; such pysanky were called "zhalobnymy" (sad) in the Sokal region.

However, there were villages where the custom did not decline but spread. In those villages, krashanky and pysanky with a red background were used less. Pysanky with a black background written in "three waxes" appeared in their place. An extremely important addition to Korduba's work are thirteen plates, which reproduce in colors more than 150 samples of pysanky from the outskirts of the northern Lviv Region.

Based on his observations, Korduba considered ornamentation on pysanky to be more important than the ritual aspects. He divided the pysanka ornaments into three main groups: geometric, plant and animal. He also included household objects and Christian symbols in the group of geometric ornaments.

Another author who described pysanky of the Sokal region, Bronislav Sokalskyi, divided the "drawings" on the egg into two types: a) straight-line geometric drawing and b) drawing with curved, wavy or “snail-like" lines.

Placement of patterns on pysanky typical of that time was most often in eight triangular segments into which the egg's oval shape was divided with two longitudinal and one transverse lines. Ornamental motifs from the aforementioned groups were placed in those fields. Of all the patterns that we see in the Korduba plates, almost half have this division. Sokalskyi, describing the writing of pysanky, mentions only this division "into eight triangular fields.” Unfortunately, he did not include any illustrations of pysanky in his work.

This scheme of distribution and arrangement of patterns on pysanky was also the most widespread in other regions of Ukraine. This division of the egg made it easier for the pysankarka to write designs on the egg's oval shape.

A very interesting aspect of Korduba's work is the recording of the names of designs, or rather the names of individual elements, which were placed into the design of a whole pysanka. The names of the designs of pysanky in the Sokal region were always n the genitive case, for example: “written with pasochky", "klynchyky", "flowers", etc. B. Sokalskyi writes that pysanky with a geometric look were named “written with krysky,” i.e. dashes. Both researchers believed that some of the geometric patterns resembled netting or embroidery.

The geometric motifs that decorated pysanky in the late 19th century were named: reshitka (lattice), pasochky (belts), kutochky (corners), koshychky (baskets), hrabel’ky (rakes), vitriaky (windmills), zvizdy (stars), rozhi (mallow flowers) and various types of crosses . All plant or flower motifs of that time were placed symmetrically in the fields formed by lines - “peredilky” (divisions) on the surface of the egg. A very popular plant motif was the "smerechky" (spruce) motif, which Korduba considered transitional from geometric to floral ornament. Other plant motifs were "leaves", "flowers", "grapes", "oak leaves" and a stylized tree of life.

Designs with animal motifs were very rare. These were stylized images of birds or parts of their anatomy such as "chicken legs", "duck feet", as well as "ram horns,” “spiders," etc.

The first hints about the changes that had begun to occur in the ornamentation of Sokal pysanky at the turn of the 19th century can be found in the correspondence of B. Sokalskyi, where he writes that "in the village of Horodylovych, older women write fewer and fewer pysanky, because their ancient patterns ("belts", "crosses", etc.) have little recognition.”

Pysanky written by young women who went to school and studied drawing gained preference. They recreated the patterns they drew at school on pysanky. In another part of his letter, the author writes that in the village of Steniatyn they draw "flowers like those found on kerchiefs.”

From this it becomes clear that there has been a change in fashion. New preferences prevailed over tradition. Belief in the magical power of pysanka symbols ceased to exist. It is possible that older women still wrote the old geometric patterns with “krysky," because it was easier, but young women and older girls began to produce amazing, fantastic flowers on eggs, and this method of writing pysanky became very popular in the Sokal region.

In my opinion, this is the only region in Ukraine where there has been such an punctillious change in the ornamentation of pysanky.

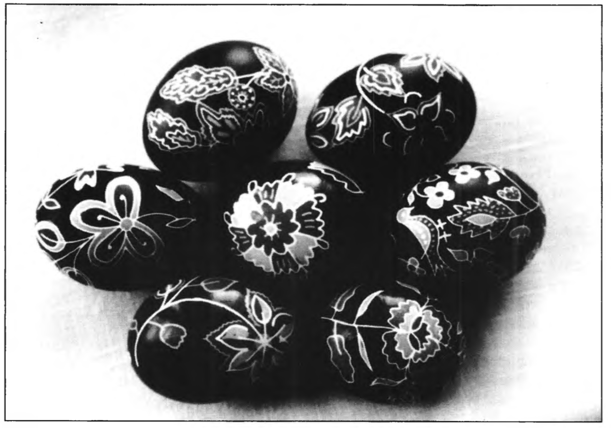

Examining the floral motifs on Sokal pysanky from the 20th century, it can be noted that they were written freely, spontaneously, probably without a preliminary pencil drawing. In some cases, we see an attempt to draw naturalistic flowers such as lilies of the valley or forget-me-nots. The most widespread were large red flowers, the contours of which were written in white; their petals and leaves were often outlined with a jagged yellow line. The red petals of the large flowers were decorated with yellow spots or dots. A very characteristic phenomenon was that the leaves were filled in half each with yellow and red color. The writing style of these floral pysanky was mainly "three waxes.” On them we see white, yellow and red on a dark, mostly black background. Pysanky with a green or other colored background were very rare.

Writing flowers on the surface of the egg without dividing it into smaller fields required great skill and ingenuity of the pysankarka. The fantastic flowers of the unevenly covered the surface of the egg, or grew out of vases in the form of a stylized tree of life. Such a pysanka had to be examined by turning the egg around.

Sokal pysanky of the early 20th century

The most talented artist, and because of that the most famous, in writing floral designs was a peasant woman from the village of Horodylovychi, Iryna Bilianska (born 1899). The heyday of her work was in the 1930s, before the war. Girls and women from Horodylovychi and neighboring villages learned to write pysanky from Bilianska, however, as Sofia Chekhovych writes: "None of them surpassed her in the artistry of her composition, in the subtlety of the selection of tones, and in the use of writing techniques."

I. Bilyanska worked out a complex dyeing process. By bleaching the eggs in cabbage kvas, she was able to get a wide range of colors. Her writing used a wax line without traditional contours. She filled the surface of the egg with garlands of small flowers and leaves, with which she wrapped embroidery designs, tryzubs (tridents), patriotic inscriptions and the inscription “Христос Воскрес” (“Christ is Risen”).

Folk art expert Demian Horniatkevych first drew attention to the work of Iryna Bilianska. He recognized that I. Bilianska "brought creativity to exceptional achievements... and created her own style that has all the signs of the latest trends, but stems from tradition..."

The heyday of floral ornaments on pysanky in the Sokal region was during the 1930s. Since then, as we know, many changes have taken place.

Many villages ceased to exist due to the Soviet era industrialization of the Sokal region. The northwestern part of Sokal was separated from Ukraine and annexed to Poland, and the indigenous population was forcibly evicted. Workers from Russia and other territories were settled in new homes in the newly industrialized region. The tradition of pysankarstvo was thus brutally interrupted — and the flowers on Sokal pysanky stopped blooming.

Original article can be downloaded here.

Tanya Osadca

Back to Sokal Home

Back to Western Ukraine Home

Back to Regional Pysanky Home

Back to Traditional Pysanky HOME

Search my site with Google