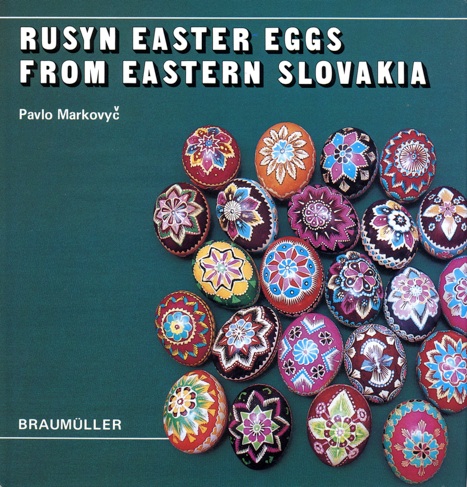

Rusyn Easter Eggs from Eastern Slovakia

Author: Pavlo Markovyč (Pavlo Markovych)

Translator: Marta Skorupsky

Format: Hardcover

Pages: 146

Language: English

Illustrations: Color plates, BW diagrams and photos

Publisher: Wilhelm Braumüller Universitäts-Verlagsbuchhandlung Gmbh. (Vienna, 1987)

Availability: out of print

Acquired: from the CRRC

ISBN: 3-7003-0695-4

TL/DR: Nice but inaccurate

The Ukrainians of eastern Slovakia are of the Lemko ethnographic group, and this is a book about their pysanky.

It is a lovely book, a translation of a Soviet-era Ukrainian-language Slovak-published scholarly work. The English-language edition is printed on much higher quality paper, with gorgeous plates and lots of illustrations, many of which are different from those in the original book. The translation is reasonably good, awkward in places but still readable. According to the introduction, there have been a few changes from the original, removing repetitive phrases and changing the author’s use of the word “Ukrainian” to “Rusyn” throughout.

Ancient Ukraine was known as Kyivan Rus, and Ukrainians have been known since by many names, including, commonly, “Rusyn.” It has fallen from usage in the 20th century, except among the descendants of Lemko emigrants, many of whom now self-identify as “Carpatho-Rusyn.” Since this book was subsidized by the Carpatho-Rusyn Research Council of the US, that is the term used throughout this translation of the book.

The introduction, as was mandatory in 1972, is a paean to the joys of the Soviet socialist regime and the wonders and progress it had wrought. Such praise is found intermittently throughout the book, as in the section on games, where the author notes:

“After 1945, the Lemko type of pysanka, which in Czechoslovakia is characteristic only among the Rusyn population of Eastern Slovakia, became widespread throughout the entire country. This occurred as a result of improved conditions for the Rusyn working woman under socialism.”

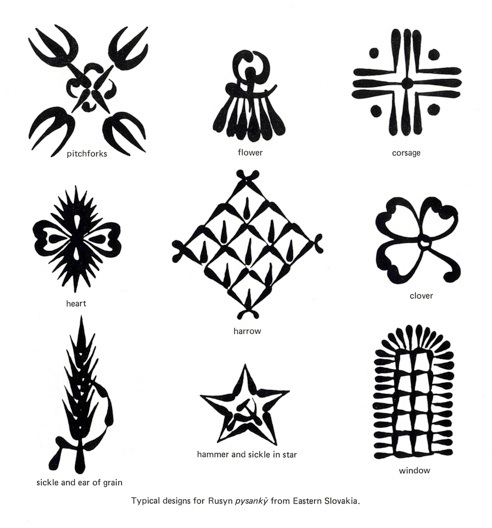

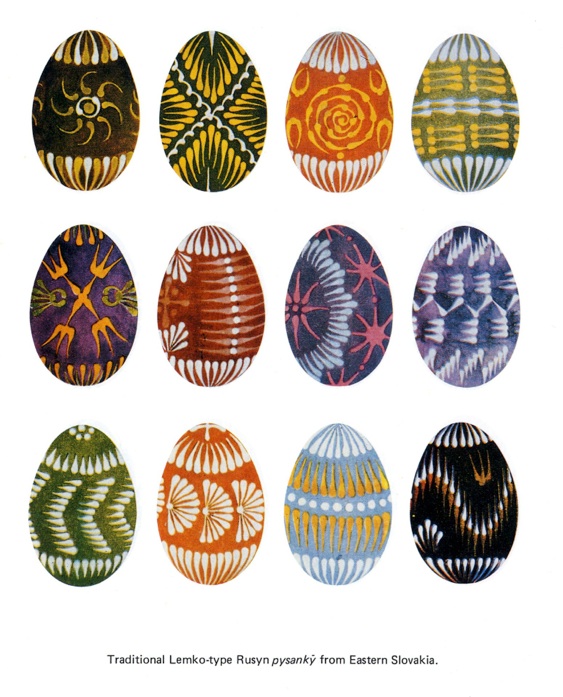

And, among the ”typical” designs for Rusyn pysanky in the plate below, there are a Soviet star, pitchforks and a hammer and sickle1. All glory to Soviet labor!

The rest of the work is a serious and masterful ethnographic work covering folk traditions, origins, symbolism, and practical aspects of egg decoration. Although there is an emphasis on drop-pull pysanky, traditional wax-resist pysanky, dryapanky, Pace eggs, applique (straw) and wax embossing are also covered.

I was particularly impressed by the sections on symbolism (which includes not only examples of symbols, but fancy charts systematizing their meanings and significance) and color (which includes folk songs and poems to help illustrate concepts). It was interesting to see photos of some of the pysanka artists, and to learn that the number of strokes on Lemko monochromatic pysanky ranges from 118 to 254, while that of dots ranges only from 2 to 81. My one quibble with the author is his conflating pysanky and krashanky (which he calls farbanky) when it comes to traditions, but it is a common mistake made by many authors. Only boiled eggs were normally used in the many children’s games he cites.

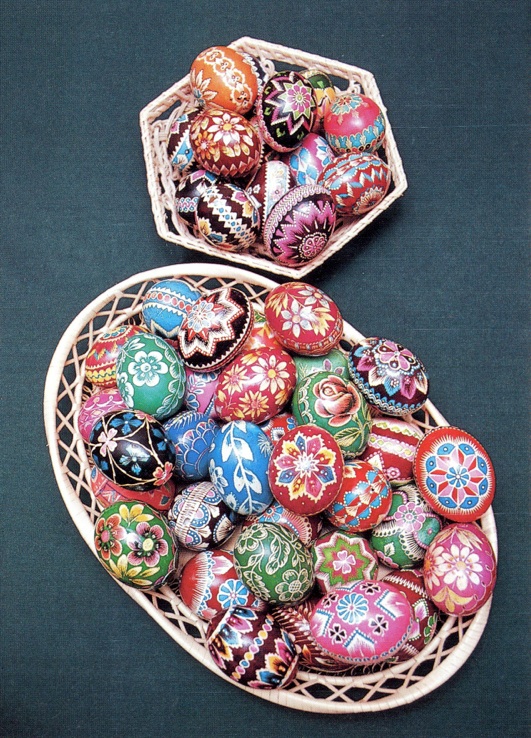

The book is generously illustrated, both with drawing and photographs. This photo shows, among others, several different styles of Rusyn egg decoration:

The colors in these examples, though, are very bright, and there are many more per egg than would be found traditionally. This is where the English version differs significantly from the original edition of the book. The earlier edition (1972) was a scholarly treatise, with more of an emphasis on traditional colors and designs. While many of Markovych’s watercolor illustrations depicting traditional pysanky have been reproduced, the photos are all new, all the older ones all having been replaced. The new photos show bright, gaudy, modern eggs (as above), rather than the more muted, simpler traditional designs. There are also many photos of the “other” styles of egg decoration, including straw applique, scratchwork, encaustic, wax pencil and other techniques which were less common among the Ukrainians, and may be more of a Slovak influence. These were not given such prominence in the earlier edition.

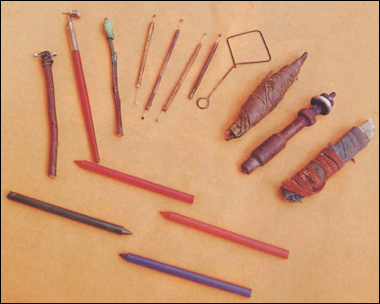

One useful addition to this edition is the photos of the tools and colorants used to create the various types of decorated eggs. Below is one example:

As I noted above, Markovych’s watercolors of traditional pysanky and their motifs have, thankfully, been preserved. The pysanky are shown both in the traditional manner:

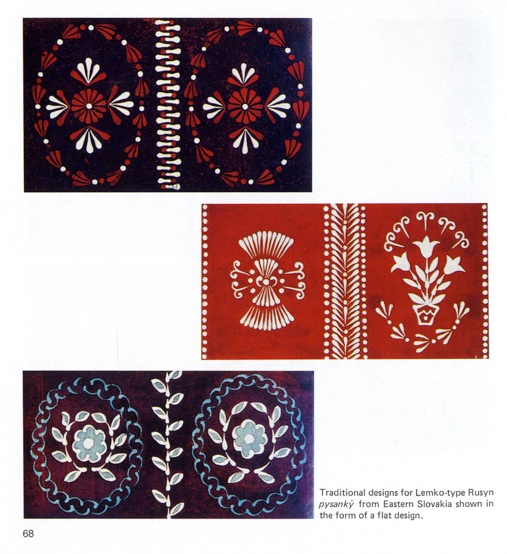

and in the more scientific flat “rolled out” manner:

All-in-all, this is a wonderful book, and I would recommend it to anyone; if you are fluent in Ukrainian, though, the original version offers more authentic photos of the pysankary and their pysanky.

___________

-

1.Back in Soviet times such interpolation of communist party motifs into folk culture was common. I remember seeing a traditional style carved plate at the Hutsul Folk Museum in Kolomyia with Lenin’s profile on it. It disappeared promptly after August 24, 1991.

Such “typical” motifs disappeared quite quickly from the entire folk repertoire after the fall of the Soviet Union–except perhaps in Russia.

Back to MAIN Pysanka Books home page.

Back to MAIN Books home page.

Back to Pysanka Bibliography.